In this blog, we will write about The Rainbow Warrior Case and will discuss the legal principles established by the France-New Zealand Arbitration Tribunal on 30 April, 1990.

Full Case Name: NEW ZEALAND v. FRANCE

Court Name: France-New Zealand Arbitration Tribunal

(Jiménez de Aréchaga, Chairman; Sir Kenneth Keith and Professor Bredin, Members)

Citation: 82 I.L.R. 500 (1990)

FACTS OF THE RAINBOW WARRIOR CASE

Rainbow Warrior was a vessel belonging to the Greenpeace International. On July 10, 1985, the Rainbow Warrior, which was due to drift to Moruroa Atoll to protest French atmospheric nuclear weapons tests there, was sunk by two bomb explosions while anchored in Auckland Harbour. The operation was carried out by the “action” branch of the French Foreign Intelligence Services, the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE) in order to restrain her from interfering in a nuclear test in Moruroa. One of the 11 members of the crew was killed. He has been named as Portuguese photographer Fernando Pereira. Two of the agents, Major Mafart and Captain Prieur, were further arrested in New Zealand and, having pleaded guilty to charges of manslaughter and criminal damage, were sentenced by a New Zealand court to ten years imprisonment. Later on, a dispute arose between France, which insisted on the release of the two agents, and New Zealand, which asserted monetary compensation for the incident. New Zealand also alleged that France was threatening to interrupt New Zealand’s trade with the European Communities unless the two agents were released. The dispute was arbitrated by UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar in 1986, and became prominent in the field of Public International Law for its application on state responsibility.

The two countries pleaded the Secretary-General of the United Nations to mediate and to offer a solution as a ruling, which both Parties agreed in advance to accept. The Secretary-General’s ruling was given in 1986 which required France to pay US $7 million to New Zealand and to guarantee not to take certain defined measures which will cause hardship and injury to New Zealand’s trade with the European Communities.

The ruling also laid down that Major Mafart and Captain Prieur were to be released into French custody but were to spend the next three years on an isolated French military base in the Pacific. The two States made ‘The First Agreement’ in the form of an exchange of letters on 9 July 1986 which required for the implementation of the ruling.

The agents were transferred on 23rd July 1986 to a French military facility and subsequently transported to Paris on the basis that they needed urgent medical attention without the consent of New Zealand. On 14 December 1987 Mafart left Hao, without the consent of New Zealand on the ground of urgent health related transfer. In both cases New Zealand requested that an independent medical examination be made. However, the French authorities notified New Zealand that Captain Prieur’s father was dying of cancer and that her immediate evacuation had thus become necessary. She was repatriated on 5 May 1988 without the consent of New Zealand and never returned to Hao.

ISSUE OF THE RAINBOW WARRIOR CASE

The main issue in the rainbow warrior case was “Whether the wrongful act of a State inconsistent with an international obligation is precluded by the “distress” of the author state if there exists ‘a circumstance of extreme peril’ in which the organ of the State has, at that particular moment, no means of saving himself or persons entrusted to his care other than to act in a manner inconsistent with the requirements of the obligation?”

RULE OF LAW

The following rules of law were applied in the Rainbow Warrior Case –

Principle of State Responsibility

The general principle is that “where a state sends its agents abroad to commit acts which are illegal under international or municipal law of the target country, it is customary for the state to take responsibility for the act and issue compensation.”

Distress as a Defence

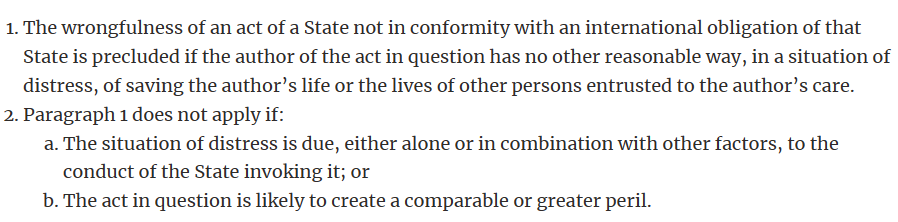

Article 24 of ILC Draft Articles on Responsibility of States For Internationally Wrongful Acts, 2001 deals with the provision of ‘distress’ which states that,

ANALYSIS OF THE RAINBOW WARRIOR CASE

New Zealand founded its arguments on the ground that France committed clear breaches of the terms of the First Agreement, which could not be excused by reference to any of the grounds recognized by the law of treaties for deviating from the terms of a treaty. Moreover, According to the law of treaties, codified in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, the principle pacta sunt servanda which means the agreement must be kept and the rules relating to the consequences of material breach and the expiry of agreements are relevant. According to the arbitrator, Max Huber, it is an undeniable principle that responsibility is the necessary corollary of rights. All international rights entail international responsibility. In the Rainbow Warrior case the Arbitral Tribunal emphasised that any violation by a State of any obligation, of whatever origin, gives rise to State responsibility.

In accordance with principles ILC Draft Articles on State Responsibility, there are three grounds for excluding wrongfulness of the act of a State, namely, force majeure (Article 31), distress (Article 32) and necessity (Article 33). In order to use distress as a defence to state responsibility of France conduct, three conditions are required:

(1) very exceptional circumstances of extreme urgency involving medical or other considerations, provided by New Zealand;

(2) the reestablishment of the original situation of compliance; and

(3) a good faith effort to try to obtain the consent of New Zealand.

CONCLUSION

The tribunal held that, the removal of Mafart was justified although it was carried out without consent of New Zealand, and not wrongful on the ground of extreme distress due to the fact that subsequent examinations showed he required medical treatment not available in Hao. But the removal of Prieur without the knowledge of New Zealand was unjustifiable and this was a material breach of the First Agreement on the part of France. Monetary compensation may be given in respect of non-material damage and the Tribunal is empowered to make an award of monetary compensation but this power would not be exercised in the present case, because New Zealand had not sought an award of monetary compensation.

Click here to read more cases about International Law.

- Summary of The Trail Smelter Arbitration Case | United States V Canada - April 8, 2023

- The Rainbow Warrior Case Summary | New Zealand V France - March 9, 2023

- The Corfu Channel Case Summary - December 10, 2022