Full Case Name: United States V Canada

Arbitrators: Charles Warren (U.S.A.), Robert A. E. Greenshields (Canada), Jan Frans Hostie (Belgium)

Award: April 16, 1938, and March 11, 1941

Citation: UN REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS, Trail Smelter case (USA v. Canada), 16. April 1938 and 11. March 1941, Volume III pp. 1905-1982

In this blog, we will write about The Trail Smelter Case and will discuss the legal principles established by the Trail Smelter Arbitral Tribunal in 1941. This arbitration case between the United States (U.S.) and Canada is the landmark judgment for the advancement of the prohibition of transboundary environmental damage in international environmental law.

Facts of Trail Smelter Case

The dispute arose between two Governments involving transboundary damage happening in the territory of the United States of America and alleged to be due to an agency situated in the territory of Canada for which environmental injury the latter has assumed by the Convention of Ottawa an international responsibility.

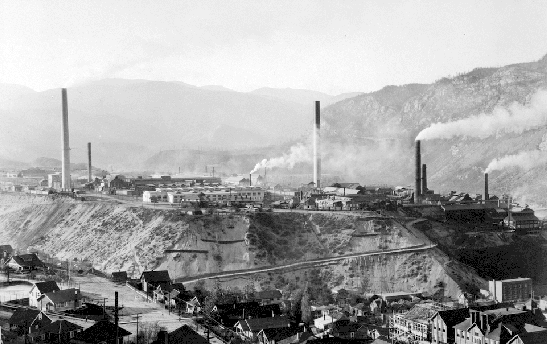

The Tribunal is made under, and its powers are derived from and restricted by, the Convention between the United States of America and Canada signed at Ottawa on April 15, 1935. In 1896 the smelter was established under the guidance of America near the locality known as Trail. The Trail Smelter was situated in the British Columbia region of Canada and in 1906, Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada acquired it and started operating it without interruption of the USA. It was located 16 km from the U.S. border of Steven County. The smelter plant was emitting hazardous fumes (sulphur dioxide) that caused damage to plant life, forest trees, soil, and crop yields across the border in Washington State in the United States. As early as 1925 complaints were made to the Trail Smelter that damage was being done to property in the northern part of Steven County. A farmer named J. H. Stroh, whose farm was located a few miles south of the boundary line, first made a formal complaint in 1926. He was followed by others, and the Smelter Company taking the matter seriously started a complete investigation. Between 1925 and 1927, stacks, 409 feet high, were constructed and the smelter expanded its output, resulting in more sulphur dioxide fumes. The higher stacks increased the area of damage in the United States. In December, 1927, the United States Government suggested to the Canadian Government that environmental damage growing out of the operation of the Trail Smelter should be referred to the International Joint Commission for investigation and report.

From 1925 to 1931, the damage had been caused in the State of Washington by the Sulphur Dioxide coming from the Trail Smelter, and the International Joint Commission advised payment of $350,000 in respect of damage to 1 January 1932. Regardless of the IJC-UC decision, the Trail smelter’s injurious operation did not change. The United States Government, on February 17, 1933, made a representation to the Canadian Government that the existing circumstances were entirely unsatisfactory, and diplomatic negotiations were entered into, which resulted in the signing of the present Convention. Through the Convention, the two countries agreed to refer the matter to a three-member arbitration tribunal composed of an American, a Canadian, and an independent chairman (a Belgian national was ultimately appointed). In its first decision (1938), the Tribunal held that harm had been caused between 1932 and 1937 and ordered the payment of monetary compensation of $78,000 as the ‘complete and final indemnity and compensation for all damage which occurred between such dates’.The Tribunal’s second decision (1941), was concerned with the final three questions presented by the 1935 Convention, namely, responsibility for, and the appropriate mitigation and indemnification of, future harm. The Tribunal then further imposed duty and responsibility not to cause transboundary harm on the defaulting state, Canada.

Issues of the Trail Smelter Case

The responsibility made upon the Tribunal by the Convention was to “finally decide” the following issues:

(1) Whether damage caused by the Trail Smelter in the State of Washington has occurred since the first day of January 1932, and, if so, what indemnity should be paid therefore?

(2) Whether the Trail Smelter should be required to refrain from causing damage in the State of Washington in the future?

(3) What measures or régime, if any, should be adopted or maintained by the Trail Smelter?

(4) What indemnity or compensation should be paid regarding decisions rendered by the Tribunal pursuant to the next two preceding questions?

Reasonings in the Trail Smelter Case

According to Brownlie, the no-harm principle is a broadly known rule of customary international law under which a State has an obligation to prevent, reduce and control the risk of environmental harm or injury to other states.

Principle 21 Stockholm Declaration, 1972

The principle has now become customary international law which is also binding on non-ratifying countries. The same principle is reiterated under Principle 2 of the Rio Declaration, 1992. According to the UN Charter and rules of international law, a sovereign state has the ‘right to exploit their own resources in furtherance to their own environmental and progressive policies, and the legal and moral duty to ensure that commercial or non-commercial functions within their jurisdiction or control do not cause injury to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.

Article 31 of Responsibility of States for Wrongful Acts, 2001 deals with provisions of reparation. According to that Article –

Principle 16 of the Rio Declaration, 1992 deals with polluters’ pay principle. According to that principle,

Analysis of Trail Smelter Case

The Trail Smelter decision has reinforced the main rule underlying international environmental law. According to this rule, a state which causes transboundary pollution or some other environmentally hazardous effect is responsible for the harm either directly or indirectly, to another state. The rule is rooted both in Roman Law and Common Law. The Latin maxim “sic utere ut alienum non laedas” which means “use your own property in such a manner as not to injure that of another” is the center of the customary rule of international law. Earlier to the 20th century, this rule was not so familiar to international law because commercial functions within a nation’s borders rarely conflicted with the rights of another. The Trail Smelter case commenced with the issue of the “duty” of states to “prevent transboundary harm” and applying the “polluter pays” principle. International law imposes on states an extra-territorial responsibility. The tribunal did not require Canada to stop the smelter plant in the Canadian State of British Columbia that released Zinc Oxide fumes in the atmosphere and caused extensive cross-border damage to the vegetation in the US State of Washington. Canada was asked to modify the manner of operation of the smelter so as not to be injurious to the US. Canada had the sovereign right to establish and operate the smelter within its territory, but it had a reciprocal duty not to infringe on the sovereign right of the US. According to the tribunal, “sovereign right excludes the usurpation and exercise of sovereign rights of another state and no state has the right to use and permit the use of its territory in such a manner as to cause injury to the territory of another state.”

The tribunal imposed a “due diligence” obligation on Canada. The obligation “not to cause serious environmental harm” was historically founded on the intention to ensure the continuing compliance of the Trail Smelter with pollution prevention measures. Due diligence is prescribed by the “Draft Articles on Prevention of Transboundary Harm from Hazardous Activities” as the main condition of intent needed to establish the liability of transboundary polluters. In the commercial world, multinational corporations have modern resources and scientific knowledge and equipment to regulate their own functions in ways relevant to concepts of “corporate social and environmental responsibility” and governments must work together with those corporations to prevent harm. Another aspect of the Trail Smelter case that remains important is it would counsel that states be held responsible for their own extra-territorial damage which results in human rights violations abroad.

The “Polluters Pays’ Principle” is the widely familiar practice that those who produce pollution as a by-product of their manufacturing activities should bear the expenses of managing it to prevent damage to human health or the environment.

Conclusion

Finally, the arbitration held that Canada as a defaulting state is responsible in international law for the conduct of the Trail Smelter Company. That’s why the onus lies on the Canadian government to look after to it that Trail Smelter’s conduct should be consistent with the obligations of Canada as it has been accepted by International law. Moreover, in furtherance of Article III of the Convention existing between the two states, the indemnity for damages should be determined by both governments. At present, the Trail smelter is still functional and It is acquired by Vancouver-based Cominco Limited, which refines Lead, Zinc, Silver, Gold, Bismuth, Cadmium, and Indium.

To read more famous Public International Law cases click here.

- Summary of The Trail Smelter Arbitration Case | United States V Canada - April 8, 2023

- The Rainbow Warrior Case Summary | New Zealand V France - March 9, 2023

- The Corfu Channel Case Summary - December 10, 2022